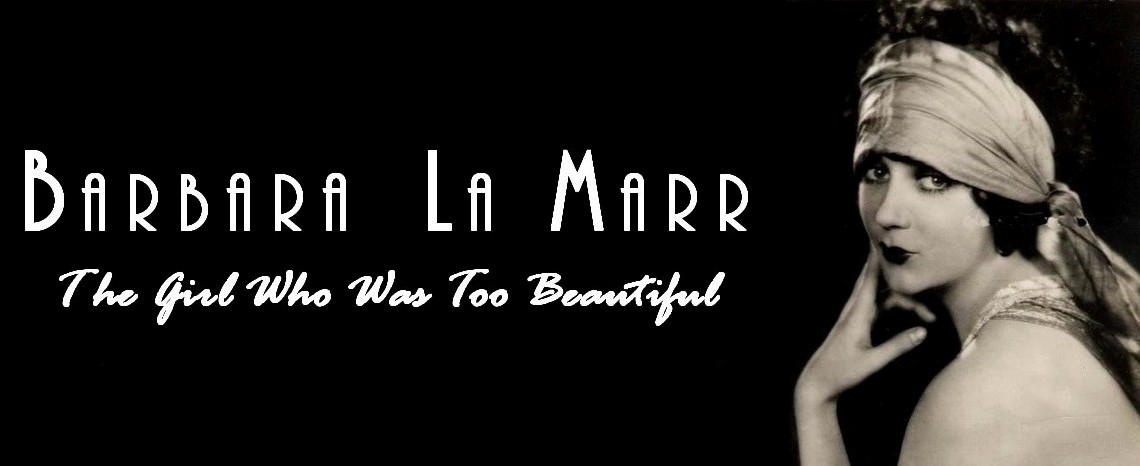

The news was received with astonishment and sorrow from the front pages of newspapers worldwide: Barbara La Marr, dead at twenty-nine on January 30, 1926, her death attributed to tuberculosis and nephritis.

As a young girl named Reatha Watson, she performed with various stock theater companies throughout the Pacific Northwest and dreamed of one day becoming a great tragedienne. In the brief span of her life, she accomplished considerably more. Her dream had not come easily, however. Strong-minded and impetuous, she was implicated in several well-publicized scandals and subsequently banned from acting in films by the Los Angeles studios at the age of seventeen. Dejected but undeterred, she achieved renown as a dancer in some of the country’s foremost cabarets and on Broadway by nineteen. Four years later, in 1920, Barbara was back in Los Angeles, earning the modern equivalent of a six-figure salary as a storywriter for Fox Film Corporation. Director Bertram Bracken encouraged her to try out for a bit part in Louis B. Mayer’s Harriet and the Piper that same year. She won the part, and her rise to ascendancy as a superstar of the silent screen was nothing short of spectacular.

Throughout 1956 and 1957, committees including the likes of Hollywood heavyweights Samuel Goldwyn, Cecil B. DeMille, Mack Sennett, Hal Roach, and Jesse Lasky convened at Hollywood’s Brown Derby restaurant to determine whom to honor with a star on the newly-proposed Hollywood Walk of Fame. Barbara La Marr was among the 1,558 motion picture, television, radio, and audio recording artists selected. Her official induction occurred at the groundbreaking ceremony on February 8, 1960. Today her star may be seen at 1621 Vine Street, a lasting testament to the twenty-six films in which she is known to have appeared, the respect accorded her by her peers, and the artistic excellence with which she inspired the world.

Barbara’s star on the Walk of Fame, located at 1621 Vine Street (near the intersection of Hollywood Blvd. and Vine) in Hollywood.

Barbara was every inch the film star. She exuded an explosive magnetism that lured men and fascinated women. Her shapely figure, exotic beauty, and smoldering sultriness earned her the distinction of being one of the silversheet’s most celebrated sex goddesses. Frequently cast in the role of a stereotypical vamp—a depraved seductress who uses her feminine wiles to undo men—, Barbara, with her versatility, inherent sensitivity, and emotional depth, nonetheless transcended her typecasting with compellingly “human” characterizations.

Below are but some of the highlights and pivotal points in Barbara’s wide-ranging career as a screen actress.

***

The Three Musketeers (1921) – Handpicked by swashbuckling action hero Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., himself, Barbara portrayed Milady de Winter, a sinister spy and enemy of the queen, Anne of Austria, in Alexandre Dumas’s classic tale of D’Artagnan (played by Fairbanks), a lowly young Frenchman whose gallantry gains him a place in King Louis XIII’s regiment of musketeers. Eternally grateful for the faith Fairbanks and Fred Niblo, the film’s director, placed in her, Barbara credited them with bolstering her determination to succeed as a film actress. Fairbanks and Niblo weren’t alone in their assessment of her potential. When The Three Musketeers entered theaters worldwide, Barbara’s beauty and screen presence evoked gasps and stunned silence. Critics also took note; “dazzling,” “unusual,” “fiery,” they wrote, applauding her vivid, wholehearted interpretation of the role.

Barbara (as Milady de Winter) and Thomas Holding (as the Duke of Buckingham) in The Three Musketeers.

***

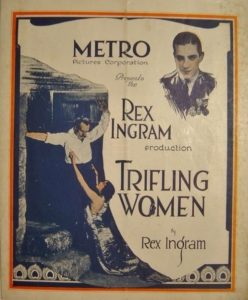

The Prisoner of Zenda (1922) and Trifling Women (1922) – Not long after The Three Musketeers premiered the end of August 1921, director Rex Ingram was scouring Hollywood for an actress capable of embodying the wicked Zareda in Trifling Women. After auditioning Barbara in November, his search was over. He offered her the part with the proviso that she first prove herself capable of handing a leading role by making good in a smaller part in The Prisoner of Zenda, a film he would direct before Trifling Women. Barbara, both thrilled and scared, realized that these films would either make or break her. She threw herself into the role of Antoinette de Mauban, the adventuress in The Prisoner of Zenda.

Barbara as Antoinette De Mauban in The Prisoner of Zenda. Pictured with Barbara are Stuart Holmes (as Black Michael, Antoinette’s lover, on far L) and Ramon Novarro (as Rupert of Hentzau, one of Michael’s men, on R in foreground). As a component of one of the film’s subplots, Antoinette ultimately betrays Michael, a traitor to the king of Ruritania, enabling the king’s rescue—all the while evading Rupert’s impassioned advances.

Ingram, filmgoers, and reviewers were impressed by Barbara’s performance. One journalist deemed her an actress of uncommon ability. Another contended that, in the midst of a stellar production that in all ways approaches perfection, she alone was worth the admission price.

Trifling Women, a film widely considered to be gruesome and overtly erotic

in its day, earned Barbara similar plaudits. Among the divergent, often heated reactions the picture generated, she was hailed as one of the most brilliant of the newer screen actresses and the most beautiful vamp on the screen. She was further noted for delivering an exceptional, flawless performance.

Barbara, as Zareda in Trifling Women, is pictured with Lewis Stone (as the Marquis Ferroni, her husband in the film) and (in upper R corner) Ramon Novarro (as Ivan de Maupin, her lover in the film). Beautiful, beguiling, and fiendish, Zareda plays her lovers like pawns, seeking wealth at any cost—until she meets her match.

***

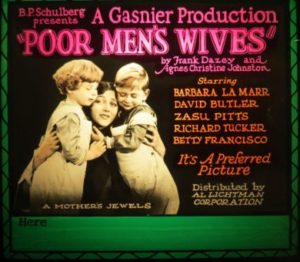

The Hero (1923) and Poor Men’s Wives (1923) – Following Barbara’s electrifying performance as a vamp in Trifling Women, director Louis J. Gasnier sensed more in her than her screen characterizations had heretofore revealed. He snapped her up for two films, affording her the opportunity to shine in non-vamp roles.

As Hester Lane, a loving, dutiful mother and respectable woman in The Hero, Barbara was entrusted with the task of creating the inner conflict of a woman torn between her feelings for her brother-in-law, a returning war hero, and remaining faithful to her dull but kindly husband. Many expressed regret over Barbara’s acceptance of a so-called “drab” role, minus the elegant gowns to which her mounting fan base had grown accustomed. Others were struck by her. Critics argued that she was every bit as beautiful in lackluster garments and lauded her dramatic range. One journalist insisted that Barbara was all anyone could desire onscreen or off.

Barbara repeated her success as the heroine in Poor Men’s Wives. Her depiction of Laura Maberne—a lower-class drudge who envies her wealthy best friend’s pampered lifestyle but realizes in the end that love, not money, trumps all—won her more raves. Journalists commended her naturalness and believability in the role, citing her portrayal as further validation of the breadth of her talent as an actress. A few reviewers believed her work in the picture to be the best she had yet done.

A glass promotional slide featuring Barbara as Laura Maberne in Poor Men’s Wives (with [L to R] Muriel McCormac and Mickey McBan, her children in the film).

***

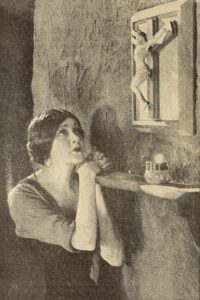

Thy Name Is Woman (1924) – The Hero and Poor Men’s Wives, to Barbara’s eventual dismay, didn’t open the way for her to consistently create more of the reality-based characterizations she most enjoyed. Audiences adored her as the vamp and she obliged them by playing vamp roles, particularly after inking a starring contract with Associated Pictures in August 1923. Thy Name Is Woman provided one of her few reprieves. Barbara lost herself in Guerita, a tormented woman who, in love for the first time—and with a man other than her husband—must summon the strength to follow her heart. The highly-charged, emotional part both fascinated and exhausted Barbara.

Accolades for her efforts streaked the trades and newspapers. Her performance in Thy Name Is Woman was said to be one of the most powerful performances witnessed in any film that year. Perhaps her highest commendation came from a San Francisco Chronicle newspaperman who likened her portrayal to “having the soul of a woman on the dissecting table, where the scalpel has been used ruthlessly.”

Barbara as Guerita in Thy Name Is Woman. She considered the role her favorite, and her work in the film to be the best she had thus far done.

***

The Girl from Montmartre (1926) – Sadly, Barbara’s career was waning by 1925. Mismanagement of her talent, a series of flops, and public backlash against screen vamps were among the main contributing factors. Her health—undermined by severe weight loss practices, emotional distress, late nights spent in clubs, and excess drinking—was also fading. Rallying valiantly, she severed ties with Associated Pictures and resolved to reclaim her career.

For her final vehicle under her starring contract with Associated Pictures, she cast her slinky gowns, feathered fans, and bejeweled headpieces aside, insisting upon a genuine character and a story with heart interest. Against doctor’s admonitions, her parents’ pleas, and all odds, she forced herself to the studio each day, considerably frail and often crippled by pain. She put her soul into the role of Emilia, a Spanish peasant of noble birth whose past as a cabaret dancer prevents her from marrying the man she loves until the film’s end.

Hellbent on completing The Girl from Montmartre, and never one to let her colleagues down, Barbara declined the production team’s offer to postpone filming for the sake of her health. (She is seen here with Robert Ellis, her villainous suitor in the film.)

While certain critics and exhibitors dismissed the story as weak and the film as ordinary, many saw something more. People marveled at Barbara’s courage and perseverance. Some remarked that an ethereal, spiritual beauty had overshadowed the illness that had diminished her once voluptuous form. Others attested to the presence of an underlying fire in her, the same vitality that had won her fame. One journalist, applauding her poignant performance, asserted that her beauty and talent appeared to have blossomed; he assured Barbara she had nothing to regret. A handful of reviewers called it the best performance she had ever rendered.

Their sentiments were lost on Barbara. She had passed away a day before the release of The Girl from Montmartre. Weeks before, the film’s producers, aware of her impending death, had alternately scrambled to get the picture into theaters and contemplated shelving it. History had convinced them that the general public tended to avoid films featuring dead stars. Barbara proved them wrong; numerous exhibitors nationwide reported packed houses and capacity business while showing the film.

***

Although a large portion of Barbara’s film work is unfortunately currently unaccounted for, some of her films (including The Three Musketeers and The Prisoner of Zenda) may readily be enjoyed today. For a listing of her extant films and where they may be viewed, refer to the filmography page.

©2015 Sherri Snyder

Notes:

“having the soul”: San Francisco Chronicle quoted in “Thy Name is Woman,” Film Daily, March 9, 1924, pg. 16.