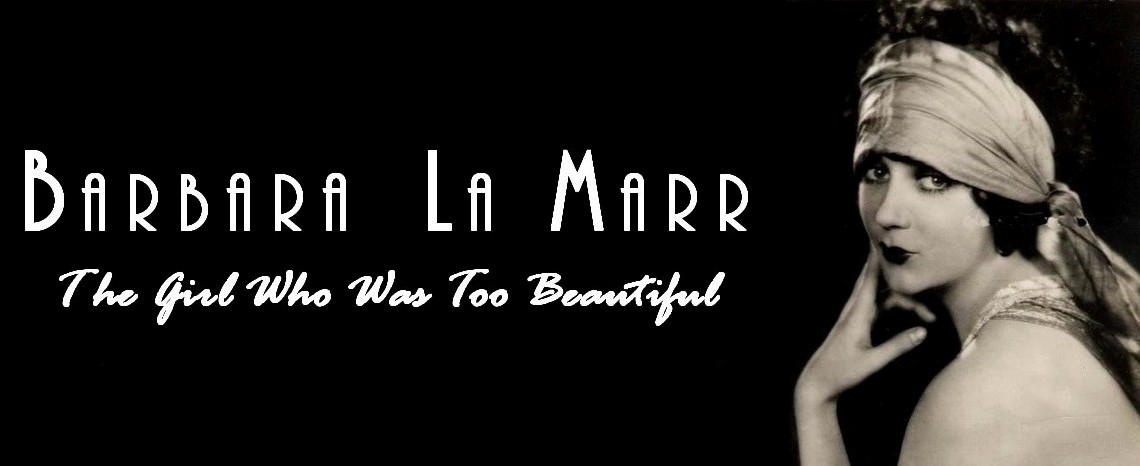

Barbara La Marr earned her “Too Beautiful Girl” title after juvenile authorities ordered her from Los Angeles on the grounds that she was “too beautiful” to be on her own in a big city. She was seventeen-year-old Reatha Watson then. It wasn’t her first appearance in newspaper headlines, nor would it be her last. After her death at age twenty-nine caused a furor in downtown Los Angeles, her publicist confessed, “There was no reason to lie about Barbara La Marr…Everything she said, everything she did, even to her dramatic passing, was colored with news-value. A personality dangerous, vivid, attractive; a desire to live life at its maddest and its fullest; a mixture of sentiment and hardness, a creature of weakness and strength—that was Barbara La Marr.”

Reatha Dale Watson made her grand debut into the world on July 28, 1896, in Yakima, Washington. She was the last child born to Rosa (Rose) Contner (spelled “Countner” in later records) and William Watson, a writer, newspaperman, and irrigationist. Reatha was William’s second child; a brother, William Jr. (later known as Billy DeVore on vaudeville stages) preceded her in 1886. Before her marriage to William, Rose evidently had two sons and a daughter with Caleb Barber, a man who left her a widow. Two of these children are more readily identifiable through available records: Henry, born 1876, and Violet, born 1880.

Young Reatha was profoundly affected by her father’s vocation. She spent her childhood and teenage years inhabiting various rental dwellings as William accepted newspaper work throughout Washington, Oregon, and California. In addition to her Catholic schooling, Reatha was absorbed by the stories her father read to the family in the evenings. She immersed herself in his extensive book collection from an early age, further honing her innate intellect. Reatha also uncovered an inborn talent and abiding passion for writing. Bolstered by her father’s encouragement, she first composed little verses and soon found great joy in penning fantasy-like tales.

As an eight-year-old girl in Tacoma, Washington, Reatha discovered what was to be another great love of her life. It struck her in a darkened theater during a performance given by the Allen Stock Company. She made up her mind then and there, she later related, to become a great actress. Reatha channeled her ardent ambitions into enacting plays at home for her family and neighborhood friends. In 1905, she participated in an amateurs’ night at the same theater in which she had seen the Allen Stock Company perform. Her recitation of a dramatic poem so impressed the audience, “Dad” Allen gave her a small part in a play and, shortly thereafter, a position in his stock company. Reatha spent the remainder of her childhood performing with stock companies, delighting theatergoers and earning plaudits in such plays as East Lynne, Zaza, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

By 1910, at age fourteen, Reatha had set her sights upon an acting career in the newly emerged motion picture industry. Her attempts to launch her career, however, were beset by frustration and discouragement. Her father opposed her career choice but nonetheless afforded her a chance to break into films. He permitted her to travel with her mother from their home in Fresno, California, to Los Angeles, and eventually joined them himself, taking a newspaper job that enabled the family to remain in the city together. But Reatha, despite her determined efforts and talent, was unable to obtain anything beyond uncredited background roles. With a weighted heart, she kept trying.

In 1913 sixteen-year-old Reatha starred in a real-life drama that rivaled the offerings at the local movie houses. It began when she inexplicably vanished from her family’s Los Angeles apartment following an encounter with her estranged half-sister. Presuming the worst, her father charged to the police station and reported Reatha kidnapped—stolen, he told authorities, by her half-sister and her half-sister’s married boyfriend. A massive search for Reatha ensued, encompassing multiple states and spawning sensational headlines. The saga continued when Reatha reappeared—unharmed—telling the district attorney and reporters of having experienced what she described as the most horrible ordeal of her life. Yet testimonies given at the preliminary hearing by her half-sister, her half-sister’s boyfriend, and certain witnesses revealed that Reatha’s story was not all it seemed. A judge ultimately halted the matter from proceeding to trial, citing a lack of supporting evidence against Reatha’s so-called kidnappers.

Another kidnapping involving Reatha soon unfolded—at least according to Reatha. Not long after her initial purported kidnapping, her father—owing to her new-found notoriety in Los Angeles—obtained newspaper work in El Centro, a remote town in the southeastern California desert, and Reatha and her parents left Los Angeles. By age seventeen, unable to tolerate the desert heat—or her overly protective parents—Reatha had returned to Los Angeles alone. When she rejoined her Los Angeles friends, she made an astonishing announcement: while away with her family, she claimed, she had been married and widowed. She reported the groom to be Jack Lytelle, a handsome, wealthy Arizona rancher. He had pursued her relentlessly, she said, but she had declined his proposals of marriage. Then, supposedly driven by desperation, he allegedly approached her in his car one afternoon as she rode alone through the desert on horseback. She described him pulling her from atop her horse and into his car, forcing her to accompany him to Mexico and to an altar. Reatha further related that, two months into their happy marriage, tragedy struck; while Jack was away attending business at another ranch, she said, she received a letter from a mutual friend, informing her of his sudden death from pneumonia.

In Los Angeles, both before and after her family relocated to El Centro, Reatha indulged in another love. As a dance craze erupted in cafes and cabarets across the nation, she assuaged her sorrows and failed ambitions on the city’s dance floors. The latest dances, as well as traditional waltzes, came naturally to her and she fast emerged as a desired presence in the most popular cafes in town. That she was underage hardly deterred her from gaining entree to such establishments and partaking of the plentiful liquor supply. Reatha’s love affair with dancing met an abrupt (albeit temporary) end when her father became alarmed by reports of her activities. He enlisted the aid of juvenile officers to force his daughter to come home. The chief officer, noting the unabated attention Reatha received from men, declared her “too beautiful” to be alone in the city and sent her back to El Centro for safety, newspapers reported.

Her banishment from Los Angeles didn’t last long—nor, for that matter, did her absence from the papers. Around two months later, Reatha, still underage at seventeen and forbidden to live in Los Angeles without her parents, persuaded her mother and father to leave El Centro and relocate with her. Increasingly desperate to emancipate herself from parental authority and live on her own, Reatha wed Lawrence Converse, a garage manager, following a courtship of less than a week. The day after the wedding, Reatha learned that Converse was another woman’s husband and a father. Converse’s declaration that he had no memory of having married Reatha was of some comfort to Mrs. Converse. Doctors confirmed what she already suspected: her husband’s irrational, immoral behavior stemmed from a head injury he had sustained years earlier. Immediate surgery was required, the doctors said, to relieve pressure on his brain and—it was hoped—restore him to his former self. To prove he wasn’t responsible for his bigamous marriage, Converse underwent the operation. His plea of innocence cost him dearly; the surgery resulted in his death. Newspapers blamed the “too beautiful” Reatha. Film studios throughout Los Angeles, stating that her scandalous escapades had been too widely advertised in the papers, barred Reatha from appearing in their pictures.

Unable to work in films, Reatha turned to dancing. She took up a dance partnership and a romance with professional ballroom dancer Robert Carville in 1915. Under Carville’s tutelage, she refined her dancing skills and her image. Reborn as Barbara La Marr, she danced with Carville in cabarets and upon stages throughout the country, including on Broadway, with much success. In addition to paired performances, their act consisted of solo interpretive numbers both choreographed and performed by Barbara. A lovers’ quarrel led to a temporary dissolution of their partnership—as well as a new dance partner and husband for Barbara. She married dance sensation Philip Ainsworth on October 13, 1916. Less than two months later, a violent argument, sparked by male attention Barbara had received, finished them. Barbara fled to Carville and soon reinstated her dance partnership with him. Ainsworth promptly filed for divorce from Barbara, citing desertion and naming Carville as corespondent. As Barbara’s marital strife played out in the papers, a conflict of a different kind exploded in the headlines. The United States had entered the First World War. Carville exchanged his dancing shoes for a pair of boots, bid Barbara farewell, and marched off in service of his country.

In need of work, Barbara partnered with comedian and veteran vaudevillian Nicholas (Ben) Deely as the female component of his three-person vaudeville act. The company hit the vaudeville circuits the summer of 1917, traversing the United States and performing comedic skits to general acclaim. Twenty-one-year-old Barbara fell in love with Deely, despite being eighteen years his junior. When the company passed through Chicago, Barbara petitioned a judge for a divorce from Philip Ainsworth and the court granted it. She was unaware that her divorce decree was invalid. Divorces awarded in Illinois at the time were contingent upon something Barbara didn’t have: a minimum one-year residency in the state. Little suspecting the future consequences of her actions, she married Deely in September 1918.

By the summer of 1919 Barbara had been forced to find another outlet for her burning creativity. Years of strenuous dancing in cabarets and unrelenting vaudeville performances had taken a punishing toll on her fragile constitution. Under doctor’s orders, she abandoned vaudeville, extinguished thoughts of ever resuming a dancing career, and returned with Deely to Los Angeles. Deely accepted work in films and Barbara succumbed to what she described as an instinctive pull toward the pen. A story flowed from her that summer. That story earned her a $10,000 contract with the Fox Film Corporation, commencing in January 1920, for six original stories. That same year, her first story, The Mother of His Children, appeared in theaters worldwide. Three more of her stories and an adaptation she wrote also graced the screen in 1920; the sixth story she was contracted to write would reach theaters in 1924. Fox furthermore entrusted Barbara with the highly specialized task of creating intertitles for several films, including her own.

Before Barbara’s contract with Fox expired, a chance encounter altered the course of her destiny. She accepted an invitation from a friend, actress Marguerite De La Motte, to visit the set of The Mark of Zorro (1920)—an invitation she had nearly declined. On the set, Barbara was introduced to Douglas Fairbanks Sr., the film’s star. Following their meeting, Fairbanks offered Barbara a screen test and supporting roles in two of his films. While working on the second of these films, the critically acclaimed blockbuster The Three Musketeers (1921), Barbara made a life-changing decision. She determined to achieve success as a motion picture actress. She later credited the on-set encouragement she received from Fairbanks and Musketeers director Fred Niblo with having influenced her resolve. Ben Deely didn’t support Barbara’s decision and, in September 1921, after a series of separations and reconciliations, they separated for the last time.

Barbara indeed made good on her promise to herself. Her meteoric career as a screen actress, encompassing five years and twenty-six credited films, included major supporting and leading roles in The Prisoner of Zenda (1922), Trifling Women (1922), The Eternal City (1923), Thy Name is Woman (1924), and The Shooting of Dan McGrew (1924). She achieved star status in 1923, inking a five-year contract with Associated Pictures Corporation for starring vehicles to be released through First National. Barbara’s curvaceous form and dark, exotic beauty rendered her most suitable to portraying vamps—shameless women who used their powers of seduction to entrap men. During Barbara’s reign as a preeminent silent film vamp, director Fred Niblo described her as possessing “the most tremendous sex appeal of any woman on the screen.” Critics simultaneously praised her emotional depth and laudable capability as an actress with such commentary as: “she earns her every close-up with real tears and real acting” and “proves beyond a doubt that she is not dependent upon slinky gowns.” When not before the camera, Barbara wrote poetry and authored at least one more (unproduced) screenplay. She was frequently called upon to help rewrite films in which she appeared, though she did not receive formal writing credit in such cases.

Through it all, Barbara’s private life striped the pages of newspapers and film magazines. “I take lovers like roses,” she confessed, “by the dozen.” She was romantically linked to leading men John Gilbert and Ben Lyon; writer, director, and producer Paul Bern; and even openly homosexual star William Haines. One of Barbara’s affairs came perilously close to obliterating her career in 1922. She became pregnant while separated from Ben Deely (by a man she never publicly revealed), concealed her pregnancy, and secretly gave birth to a son. To avoid a career-damning scandal, she staged her son’s adoption in a Texas orphanage and presented him to the world—and inevitable reporters—as her adopted son, Marvin Carville La Marr. More headlines soon followed. In May of 1923, having discovered that her divorce from Philip Ainsworth wasn’t finalized until after she had married Deely, and believing her marriage to Deely therefore null and void, Barbara wed western star Jack Daugherty. Deely, presuming himself legally married to Barbara, filed a divorce suit against her, naming Daugherty as corespondent. Deely’s attorney, Herman Roth, amended Deely’s complaint against Deely’s wishes, adding the names of multiple men (some of them prominent members of the film industry) with whom Barbara had allegedly been intimate during her marriage to Deely. Unknown to Deely, Roth then presented the bogus document to Barbara’s manager, Arthur Sawyer, and demanded $25,000 in hush money to prevent it from reaching the newspapers. Acting with the district attorney’s office, Sawyer set a trap for Roth, precipitating the attorney’s arrest for extortion. The maelstrom and attendant publicity unleashed by Deely’s divorce suit and Roth’s trial took an enormous emotional and physical toll on Barbara. Her marriage to Daugherty dissolved less than a year later. As the public began associating Barbara with her onscreen persona, a banning of her films occurred. She began slipping from public favor in 1924 and her career faltered.

Barbara’s health was unraveling by 1925. Several factors contributed to her demise. True to her intense passion for life and propensity to work hard, she once declared that she had better things to do than sleep more than two hours per night. Her late nights spent in clubs “burning the candle at both ends” and an unyielding work schedule were a blight upon her steadily weakening lungs. Drinking binges and extreme weight loss methods added to the mix. She collapsed on the set of her final film, The Girl from Montmartre (1926), that October, afflicted by incipient pulmonary tuberculosis. Aware of her impending death, she relinquished her three-year-old son into the care and keeping of her friend, actress ZaSu Pitts. (Pitts and her husband, Tom Gallery, eventually adopted the boy, renaming him Donald Gallery.) Barbara passed away in Altadena, California, on January 30, 1926, at age twenty-nine, her death a combination of pulmonary tuberculosis and nephritis.

Barbara was a sensation even in death. As she lay in state in Los Angeles, an estimated 120,000 mourners visited her casket—filmdom’s biggest stars as well as ordinary folk who had, in varying ways, been touched by her existence. Echoing the sentiments of those affected by her talent, kindness, and fathomless generosity was a red rose and accompanying note, brought to her casket by a twelve-year-old girl. “To my Beautiful Lady whom I have longed to meet,” the note read in part, “may my life be as lovely and unselfish as yours has been.” Barbara rests in a crypt behind the inscription “With God in The Joy and Beauty of Youth” at Hollywood Forever Cemetery—remembered by all who loved her as a woman and soul who was “too beautiful.”

©2013 Sherri Snyder

Notes

“There was no reason to lie”: Ennis, Bert, “Meteor Called La Marr,” Motion Picture, February 1929, pg. 40.

“the most tremendous sex appeal”: “What Makes Them Stars? ‘Lure!’ Says Fred Niblo, Photoplay, November 1923, pg. 116.

“she earns her every close-up”: “‘Dan McGrew’ Fascinates New York Theatre Crowds,” Moving Picture World, June 28, 1924, pg. 817.

“proves beyond a doubt”: “National Guide to Motion Pictures,” Photoplay, March 1923, pg. 66.

“To My Beautiful Lady”: “Baby Rose Dwarfs Floral Bier,” Los Angeles Times, February 3, 1926.