The vamp first emerged on the screen in 1915. She came in the form of Theda Bara in A Fool There Was, a film inspired by Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “The Vampire.” She was a shocking figure: a woman who deliberately uses her femininity to ensnare men. To some, she was a titillating deviation, the antithesis of the standard saccharine heroine. To others, she was cause for alarm, an additional threat to society’s diminishing Victorian morals. To film producers, she was gold, the precursor to a new breed of screen goddess.

In 1922, Barbara La Marr secured her launch to superstardom when she played a vamp in Rex Ingram’s Trifling Women. Her portrayal of a cruel sorceress who plays men like pawns solidified her image as one of the silent screen’s leading temptresses. At first, Barbara welcomed the opportunity to play vamps. “I’m not silly enough to pretend I’m an ingénue,” she conceded. “It isn’t my line—on or off the screen. I don’t want to be an ingénue. I just want to be a woman.”

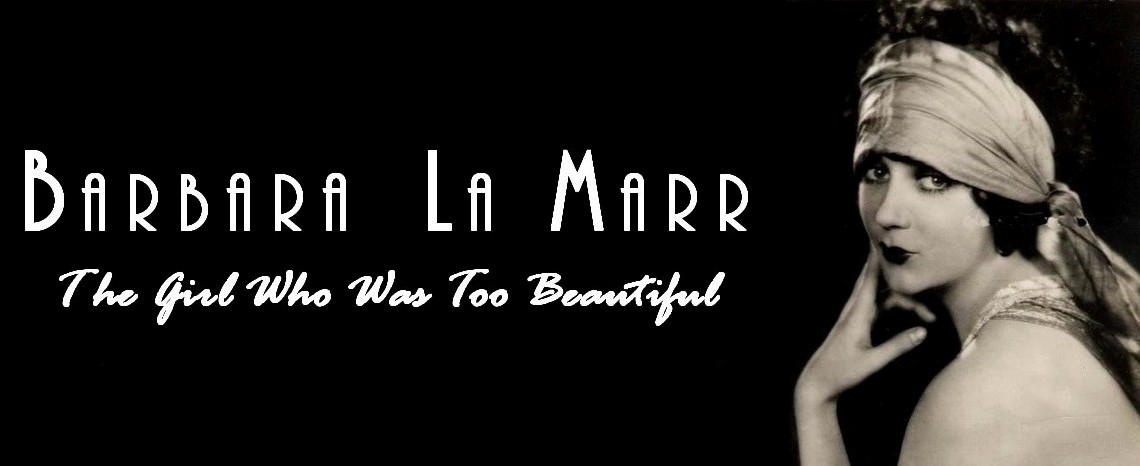

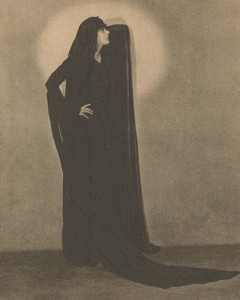

Barbara could indeed vamp with the best of them. Director Fred Niblo once marveled that even a bad dressmaker couldn’t make her look virtuous. Barbara likewise quipped that a true vamp was not dependent upon her bee-stung lips or the clinging gowns, trailing hemlines, and jeweled headpieces in which she was typically costumed. “It’s the look in the eye that does it,” she insisted. Yet Barbara’s style of vamping went beyond the popular conception of the vamp as a dimensionless caricature. An actress of true substance, she alternately infused her roles with sprightly comedic touches and, more often, gripping, heartfelt emotion. She, like the women she portrayed, was enshrouded in an aura of mystery. “She is made for lurking tragedy,” writer Willis Goldbeck mused in the November 1922 issue of Motion Picture Magazine, “…one feels the beat of ravens’ wings about her…her radiance is that of moonlight in the heavy shadows of the night…Calypso she is, burning with the flame of subtle ecstasy.”

Even so, reporters and magazine columnists, upon meeting Barbara in the flesh, were pleasantly startled. They were hard-pressed to find the slightest trace of the wicked ladies she enacted in films. Adela Rogers St. Johns recalled how Barbara’s genuine charm and captivating wit disarmed even the most hardened newspapermen. When one interviewer pressed Barbara to reveal something unusual about herself, she offered to stand on her head. Los Angeles Times reporter William Foster Elliot, struck by her sincerity and directness, commented, “She is remarkably straightforward and man to man in her attitude,” and “…really human despite the exotic bunk.”

Barbara eventually tired of playing wayward women and shunned vamp roles altogether. She yearned to play the more sympathetic roles she had proven herself capable of in such films as Louis B. Mayer’s production, Thy Name Is Woman (1924). By 1925, public tastes were similarly shifting and fun-loving flappers began eclipsing vamps as the newest idols of the silver sheet. Barbara, inextricably linked to her naughty onscreen image and declared washed-up in the trade magazines, fought for one final chance.

With her health failing and less than a year to live, she was given that chance. She was determined to see it through…

©2013 Sherri Snyder

Notes:

“I’m not silly enough”: La Marr, Barbara, “Why I Adopted a Baby,” Photoplay, May 1923, pg. 31.

“It’s the look in the eye”: Drummond, Joan, “Beautiful Barbara,” Pictures and the Picturegoer, April 1924, pg. 44.

“She is remarkably straightforward”: Elliot, Foster William , “Not Like the Fan Stories,” Los Angeles Times, September 17, 1922.