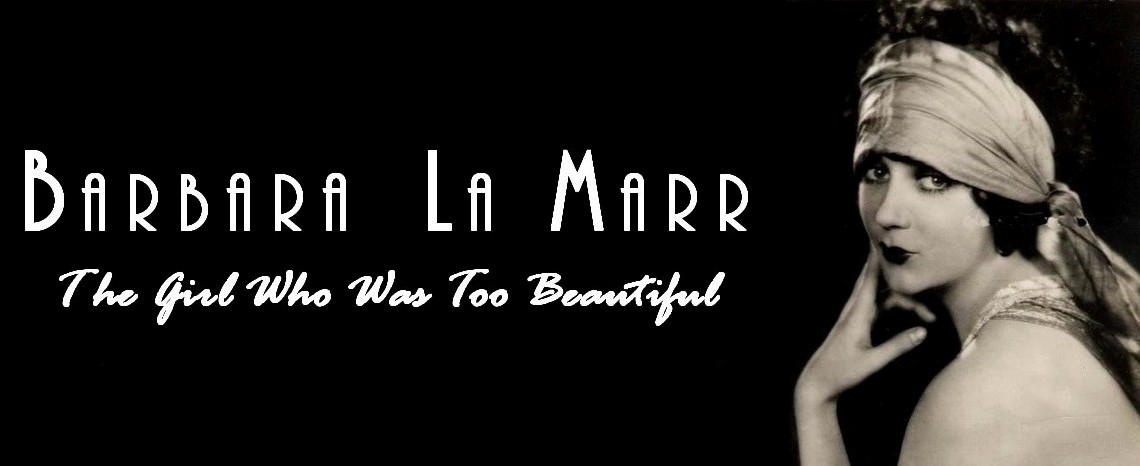

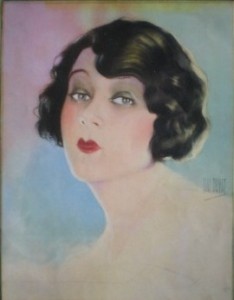

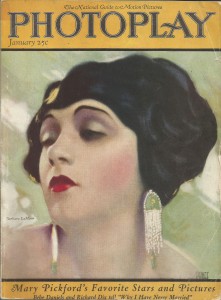

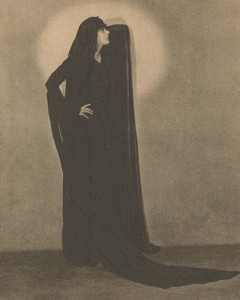

At the height of her fame in 1924, Barbara La Marr reportedly earned the modern equivalent of over $30,000 per week as a reigning vamp of the silent screen. Never far from her heart, however, was an inherent compulsion to express herself through the written word. She first put her thoughts to paper as a young girl, composing little verses and short stories. As a young woman, her inner musings took the form of poetry, pouring from her, she said, when she was so consumed with emotion that she just had to have an outlet. Her very first full-length story caught the attention of Winfield Sheehan, general manager of Fox Film Corporation, and won her a contract with Fox in 1920. Fueled by her incredible life experiences, Barbara ultimately penned five original stories and one adaptation for Fox. She put her writing talents to further use crafting intertitles for Fox films and, later, by doctoring scenarios for other studios’ films in which she played starring roles.

All the while, poetry remained her favorite medium of literary expression; to her it was “the freest of the free.” When not before the camera, Barbara sometimes sat on the sidelines of film sets, transcribing her heartfelt feelings into verse and scribbling story ideas. She vowed to one day return to her typewriter, when her career as a film actress had “gone by with the glories.” Sadly, her tragic, untimely death in 1926 at the age of twenty-nine cut short her aspiration.

The six films Barbara wrote for Fox have yet to be located by film preservationists. For now, her writings live on in her poetry. Three of her poems, written before the breakdown that resulted in her death, appear below.

Are You—?

by Barbara La Marr

.

Why should I—who worship Thought—

Unthinkingly bear my Soul unsought,

Dreams that memory cannot dim—

Why should I speak to you of HIM?

.

Why should I tell you all these things—

Of hours when Passion’s wearied wings

Folded beneath a mauve grey sky

Of dawn—that ever means “Good-bye?”

.

Of strange, mysterious, wonderful nights

When I have tasted the gods’ delights;

Of lips I have kissed, and kissing burned—

Of loves I have left and loves returned.

.

When dreaming and close at my side

I felt the urge of Passion’s tide,

I closed my eyes and infinitely sad,

Dreamed of that which I have never had.

.

But why should I—who worship Thought—

Bear my Soul to you unsought—

Telling of dreams Time cannot dim,

Unless—perhaps—that you are him!

*

.

Love and Hate

by Barbara La Marr

.

I love you—

Your lips, your hair, your eyes,

Your willful, reckless, tender lies.

I hate you!

.

I hate you—!

Your smile, your curls, your glance,

You pagan worshipper of Chance…

I love you!

*

.

Moths

by Barbara La Marr

.

Moths?— I hate them!

You ask me “Why?”

Because to me they seem

Like the souls of foolish women

Who have passed on.

Poor illusioned, fluttering things

That find, now as always,

Irresistible the warmth of the

Flame—

Taking no heed of the warning

That merely singed their wings

They flutter nearer–nearer—

Till wholly consumed

To filmy ashes of golden dust.

Foolish—-fluttering—-pitiful things—

Moths! I fear them!

Yet I watch them fascinated

And realize—many things.

Perhaps they are not useless

Nor the message they convey

To me, a futile one.

They make me see the folly

Of seeking that which it seems

Women were created for—

The futility, the uselessness of longing—

Perhaps you do not understand,

But—

Moths!–I hate them!